Lab Pasteurized Count for Estimating Bacteria in Raw Milk

The Lab Pasteurized Count (LPC) estimates the number of bacteria in a raw milk sample that can survive the pasteurization process. Most bacteria are destroyed by pasteurization. However, certain types are not.

(Source: Journal of Dairy Science 92(10):4978-87)

Lab Pasteurized Count test determines bacteria that are not natural

Raw milk can be contaminated by various microorganisms that originate from multiple sources. Therefore, determining the cause of bacterial defects in milk requires tests that select different types of bacteria since high counts can result from a combination of factors. LPC is one test that determines bacteria that are not considered to be the natural bacterial flora (those originating in the udder) of the cow.

Psychrotrophic bacteria in pasteurized milk

The thermoduric bacteria most significant to the dairy industry are spore-formers. The heat-shock from pasteurization causes the spores to outgrow. These heat-resistant psychrotrophic bacteria can continue to grow in pasteurized milk at refrigeration temperatures, causing spoilage that results in shortened shelf-life.

Many dairy processors have specifications for spore-forming bacteria that impact premium payment for the producer. High LPC raw milk will influence the final product’s specifications. For example, processors of dried milk are likely to have specifications for low LPC.

The correct procedure for LPC

According to Cornell University’s Dairy Foods Science Notes 9-28-08, the LPC procedure requires milk samples to be heated to 62.8°C (145°F) for 30 minutes, which simulates batch pasteurization.

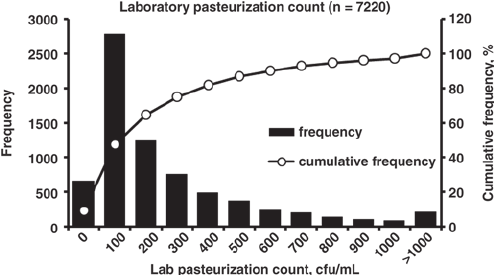

Bacteria that survive the heat treatment are then enumerated using the standard plate count (SPC) procedure. LPCs are generally much lower than SPCs, with counts > 200-300 deemed high.

The natural bacterial flora of the cow and those associated with mastitis are generally not thermoduric, although there may be a few exceptions.

High LPCs are most often associated with a chronic or persistent cleaning failure in some areas of the system and from soiled cows or other environmental contamination sources. These sources may include leaky pumps, old pipeline gaskets, inflations and other rubber parts, and milkstone deposits.

The farm may not be the only source of spore-forming bacteria. In addition to sampling at the farm for LPC, samples should also be taken at the plant. Any raw milk handling equipment can contribute to high LPC.

Read our earlier post, The Benefits of Low Spore Milk Production, to learn more.