Impact of Bacteriophages in Dairy Processing – Part 1

The quality of milk can be negatively impacted by multiple sources of contamination in a dairy processing plant. Previous blogs focused primarily on microbial contamination of raw milk caused by various bacteria.

For products such as cheese and yogurt, starter culture bacteria play a positive and essential role. However, the fermentation function of starter cultures can be threatened by another microbial contamination, bacteriophages, or phages as they are commonly called.

In this post, I’ll focus on the importance of detecting and managing bacteriophages to avoid detrimental impacts on the quality of those cultured dairy products.

“Within an increasingly competitive landscape, dairy processors must ensure their products are of the highest quality to stay ahead in the market.” Dairy Foods, Take a Proactive Approach to Phage Management in the Dairy Plant

What are bacteriophages (phages) and their impact on dairy product production?

Dairy Connection, Inc. defines bacteriophage, or “phage” as it is often abbreviated, as a commonly occurring environmental virus that is in the air, on plants, animals, and liquids.

Bacteriophages cannot grow on their own; they need a single host culture or bacteria to grow. Starter culture bacteria used in cheese and fermented dairy product production are a potential host. These starter cultures usually have one main goal: to grow and produce lactic acid, done in part by converting milk sugar (lactose) into lactic acid.

When bacteriophage is introduced into the starter cultures, it interferes with the production of lactic acid and texture for yogurt or cheese. Phage infects the bacteria, changes the function of the culture and ultimately kills it.

The invaded culture then reproduces more bacteriophages, and the new phage is ultimately released into the environment. Phage can quickly kill a starter culture, resulting in no acid or flavor production in the cheese or no coagulation in yogurt, buttermilk, or sour cream production.

Bacteriophages are uninvited guests in dairy processing

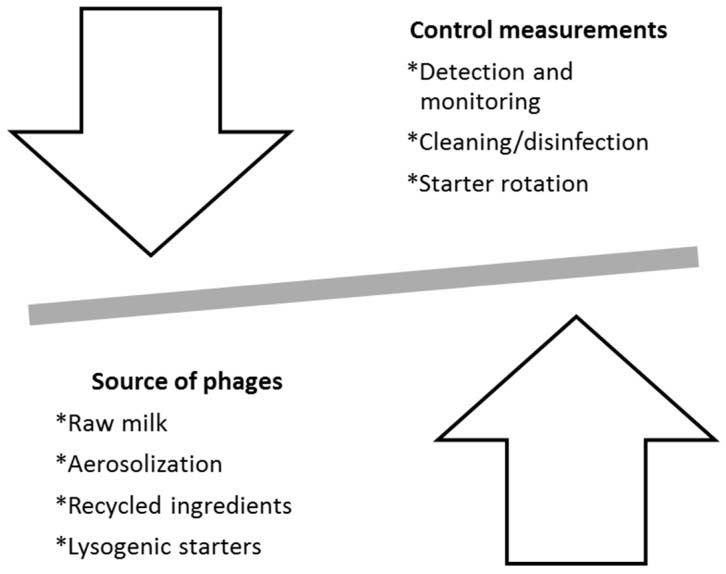

The starter cultures infected with phages are the main causes of fermentation failures in the dairy processing industry. An outbreak of phages can cause significant economic losses from lower quality products or even total production loss. Therefore, close monitoring for early detection of phages and stopping the propagation are critical in reducing losses.

Source: Bacteriophages in the Dairy Environment: From Enemies to Allies, National Center for Biotechnology Information

Phage invasion detection and the consequences

A phage infection will cause acid production to slow down and eventually stop. It may impact multiple vats unevenly. While the acid production in the first vat may be okay, in successive vats it begins to slow down until it stops.

In the case of fermented milk products, the acid production stops altogether, causing a lack of coagulation, or the pH may drop down as normal, but the texture of the fermented milk is very grainy with excessive whey-off.

“Despite extensive efforts, however, phage infection of starter lactic acid bacteria (LAB) cultures remains the most common cause of slow or incomplete fermentation in the dairy industry, and both researchers and industrial technologists are aware of regular, although unpublished, cases where phage infections actually cause product downgrading.” (Source: Bacteriophages and Dairy Fermentations)

Once phage is present in the starter culture, it is usually too late to salvage the fermentation. There is no way to reintroduce culture into cheese or to effectively add it to fermented products without causing structural damage to the milk protein. The cultured dairy products must be discarded or downgraded, which consequently leads to profit loss for the dairy processor.

Confirmation of a suspected phage invasion is made through a sampling of the whey or milk and then testing to determine which specific culture is being affected by a suspected bacteriophage virus. Rotating different strains within a culture series provides a break in the cycle, as any specific phage is only able to infect one culture strain.

Quality management for bacteriophage is multipronged and takes due diligence. According to Dairy Foods, Take a Proactive Approach to Phage Management in the Dairy Plan, phages are extremely heat resistant, due to their thermal stability, so the standard HTST (high temperature, short time) pasteurization stage during milk production does not eliminate them.

They can also withstand the impacts of freezing, drying, salt, and ethanol. Although it may be difficult to eliminate or prevent altogether, bacteriophage can be controlled through proper cleaning, sanitation and regular rotation of cultures.

“It is much easier to prevent phage than it is to rectify the problem once a bacteriophage takes hold in your production area.” Source: Dairy Connection, Inc., Getting Technical: Phage.

In Proactive Bacteriophage – Part 2, I’ll explain how a closed aseptic inoculation system can help to proactively prevent phage invasions during the production of dairy products.

Stay tuned for that post coming in November.